Nigel Bell outside his Katoomba studio (Liz Durnan)

Story by Liz Durnan

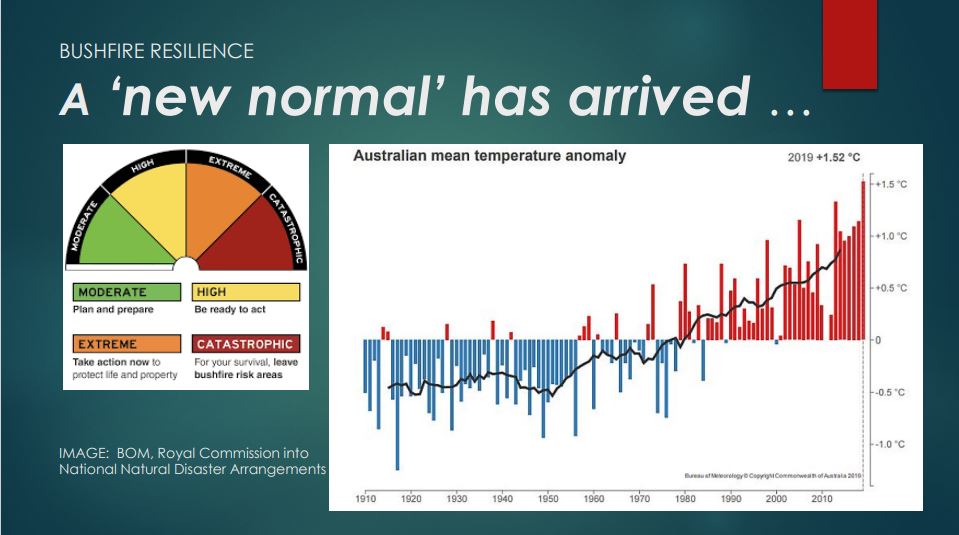

It’s a dream for many of us: a home among the gum trees, lounging on an elevated timber deck. But turning that dream into a reality in one of the most bushfire-prone regions in the country can be fraught with complexity. Here, architect Nigel Bell helps us navigate the fundamental design principles when building or renovating for bushfire resilience.

In the aftermath of Victoria’s catastrophic ‘Black Saturday’ bushfires which killed 117 people, Katoomba architect Nigel Bell facilitated the recovery and rebuild of one of the worst affected towns, Marysville, where fires took 43 lives and destroyed more than 400 homes.

With the crucial lessons from these 2009 fires and previous expertise as an architect specialising in designing for bushfire and climate change, Nigel and landscape architect Sue Bell, developed a workshop, Bushfire Resilient Design – Home and Garden which they hosted at Nigel’s Katoomba studio.

Slideshow from the Bushfire Resilient Design – Home and Garden workshop. Courtesy of Nigel Bell

Nigel outlined the design fundamentals for anyone wanting to build or retrofit a home in bushfire-prone areas, which is almost all of us who live here in the Blue Mountains.

“We are in the front line when it comes to having to consider bushfires,” Nigel says. “74 per cent of all properties in the Blue Mountains are officially bushfire affected.”

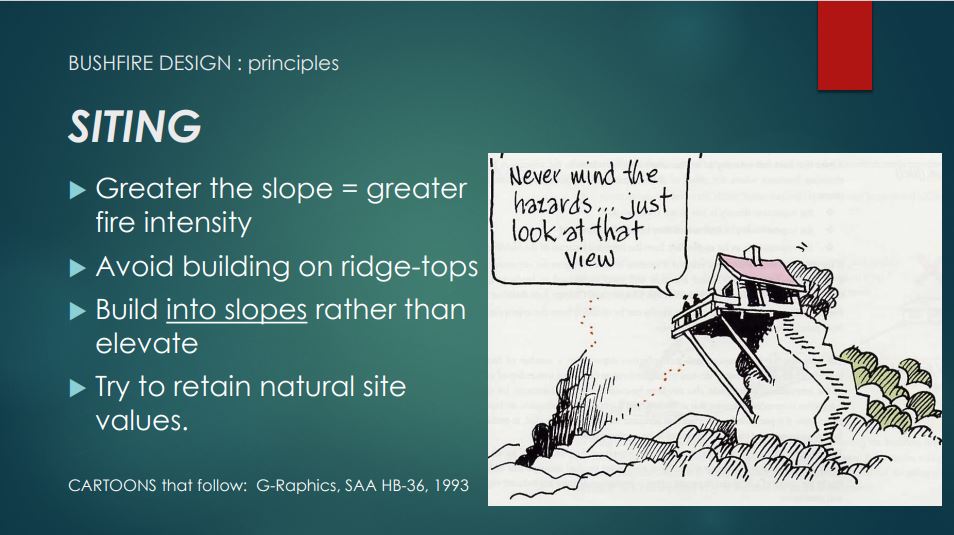

The first thing to consider, before building or retrofitting, is where a property is in relation to vegetation and bushland, and the slope of the land.

“Because the fundamental is that a fire will double in speed and intensity with every extra 10 degrees of slope,” Nigel says.

Slideshow from the workshop. Illustration by Greg Gaul

“And of course, in the Blue Mountains, we’re living on top of the ridge and the bushland is below us. When a fire starts, it travels with increasing speed up the hillside. The flame is leaning towards buildings, particularly if you’re building high, which is not a good idea. Build low into the ground wherever possible.”

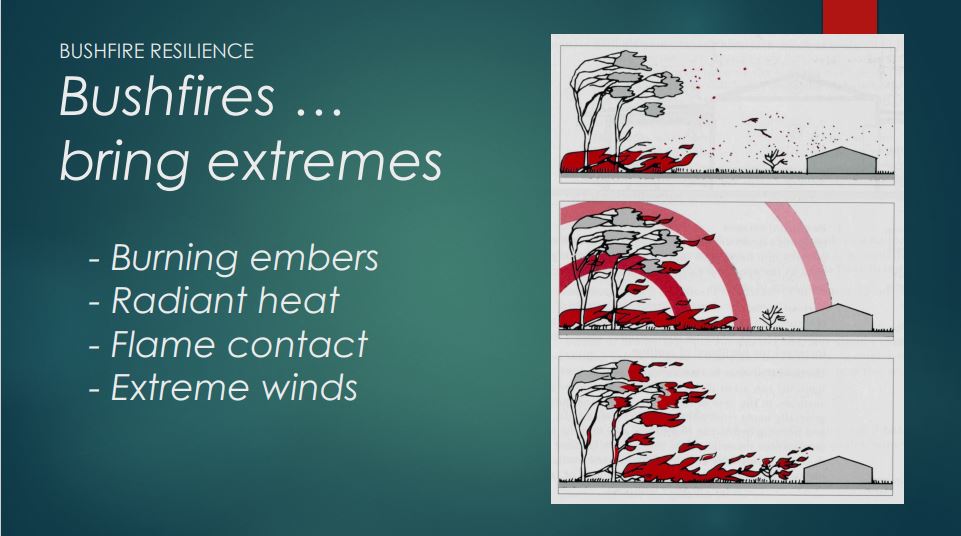

What Nigel emphasises throughout this workshop is the importance of understanding that it’s ember attack – not flames – which most often ignite buildings. These may come ahead of the fire or they may follow hours, or even days, later.

“It’s burning embers that people need to keep in mind when they are designing, selecting materials and thinking about what’s around their house. Consider what embers will do on a timber deck. They can ignite a doormat and slowly burn away until it ignites the door and becomes unstoppable.

“With extreme winds, radiant heat and burning embers, it’s quite a combination that our buildings have to deal with.”

Slideshow from workshop. Illustration by Greg Gaul

When Nigel visited Marysville in the immediate aftermath of the 2009 fires, the community and agencies faced difficult decisions about how to rebuild the town: where to build, how to build and in some cases, whether to build at all.

Understandably, the town was still in shock and there were mixed feelings from many concerned, but a ‘revisioning day’ was held for the community to have their say about expectations for the future.

“We had to try to be positive and give people hope,” Nigel says. “We had 300 or so people turn up and close to 50 volunteer facilitators.

“We employed very distinct processes to work through cathartically, from the upset, the tears, the lament, into more positive territory, in a considered and deliberate way.”

Months later they held a design ‘charette’, which is a collaborative, community-driven planning and design process.

“Instead of calling in the high-powered designers from the capital cities, the people were directly involved in their own community recovery. And that has been part of the cathartic rebuilding.’

A combination of government agencies and local people participated in workshops for two and half days to discuss the fundamental issues, while a group of architects, planners, designers, engineers, water specialists and landscape architects listened in and worked on new design principles for the town.

This method of collaboration, Nigel says, was so much more inclusive, with the voices of those affected listened to and considered for future planning.

“Instead of the traditional way where angry and loud voices dominate and most people don’t get a chance to speak or they’re too intimidated, everyone has an equal voice and with good leadership, you get breakthrough solutions.”

The lessons from those workshops not only helped to rebuild Marysville and other communities, they are now informing Nigel’s workshops, including this one.

“The principles were clear in that town, in that the higher up the hillside you were, the more risk to your house.

One home that survived those fires stands out in Nigel’s memory: “It was cut into the hillside, and made of non-combustible, concrete blockwork, aluminium window frames and toughened glass windows.”

While all these elements played a part, Nigel credits the sprinkler system fitted by the owner as the main reason for the home’s survival: “A whole mist of water surrounded the building when the fire and burning embers passed through.”

Other houses that survived sat in gullies. Though the creek beds were dry, the remnant moisture was enough to save the houses, as the fire raced up the hill and took out other homes.

This leads Nigel back to the importance of location and the relationship of land and vegetation as a starting point. Next comes the form and materials of construction.

Slideshow from workshop. Illustration by Greg Gaul.

One of the key principles of designing to withstand bushfire is simplicity – of floorplan and roofs.

“If you have a house with all kinds of angles and kinks, that’s where the embers are going to catch,” he says. “Whereas, if you’ve got a more aerodynamic house on plan, but also in roof form, there’s a very good chance that the burning embers will continue on and not get caught.”

Complex designs can include dormer windows and gable roofs with tiles, where embers can get caught and ignite. This often happens underneath the roof and isn’t detected until it’s too late and the ceilings start to collapse.

Another key design principle comes down to the choice of materials. This is obviously limited by budget and the fire rating which every property is bound by – the Bushfire Attack Level, commonly known as the BAL rating.

BAL, downloaded from What is a BAL ? (Bushfire Attack Level) – Bushfire Prone Planning – BAL Assessments

When retrofitting or building, people need to think carefully about the recommendations, says Nigel, and it’s just as important for older properties, with one major weak point being windows and doors.

“Covering the entire window frame with metal flyscreens alone will cut down the radiant heat on the glass by up to 50 per cent. Then embers aren’t going to fester away in the corner of timber windows and doors.”

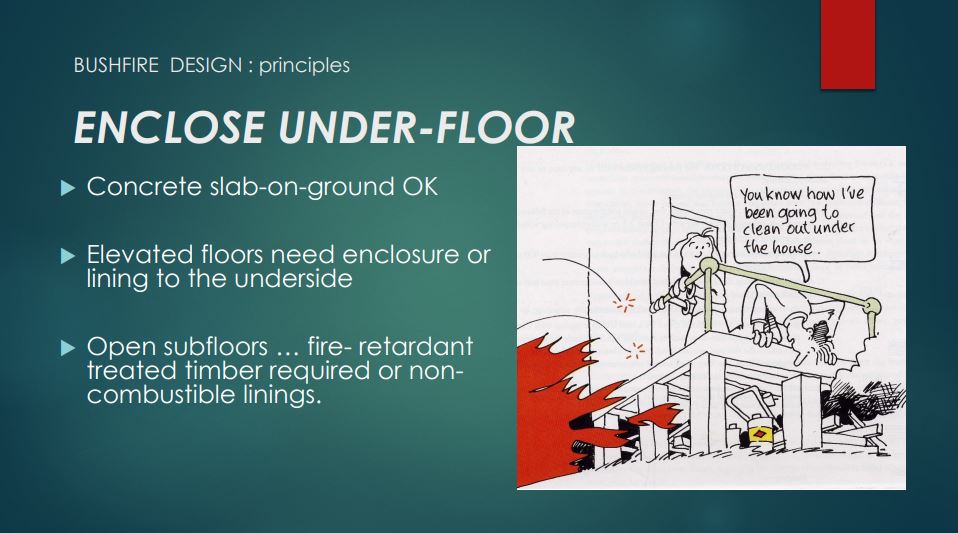

For existing homes, many timber decks would no longer be admissible in today’s restrictions. If you already have one, like the one Nigel points to in his own home, there are ways to make it safer without removing it completely.

“I’m not about to change that immediately but I will be putting a little corrugated metal skirt around the underside so that embers can’t get in underneath the deck.”

Slideshow from workshop. Illustration by Greg Gaul

It’s also important for people to reconsider what they store under the timber decks of elevated houses. Fuels or motor mowers containing fuel are definitely a no-no.

Materials for gutters are important too – metal guards and no timber thermoplastics.

While it’s not always possible to give hard and fast rules, because all properties will differ, as will all bushfires, there are a variety of bushfire attack mechanisms. “You just need to think where you are and what’s best in your particular circumstances,” Nigel says.

Nigel covers many of these latest mechanisms in the workshop, including sprinkler systems, metal shutters for windows and doors, even private bunkers (though many of these are not approved by Australian Standards).

Of course, the issue for many people with installing such mechanisms, and the restrictions on building materials, is the often prohibitive cost when building in high-risk areas.

“Unfortunately, no matter what you do, it is significantly more expensive if you’re in a high to extreme BAL area,” says Nigel. “It’s inevitable you will be paying considerably more than a standard expensive house price.

“The regulations are highly specific to what the BAL rating is. The windows, the doors, the decking, the wall materials, all require a fire rating before you will get permission to add to your home or build a new home.”

Nigel advises clients to consider moving their future home further away from native vegetation. Sometimes he may even ask them to re-consider building altogether.

“In some cases, I’ve said: ‘Look, I frankly don’t want to be involved in this project because you’re living along the edge of a distant ridge away from the main transport corridor, and you’re living in a bad bushfire situation.’”

Harsh as it might sound, it makes sense when you consider how closely Nigel worked with the Marysville recovery.

Slideshow from workshop. Illustration by Greg Gaul

Whether building from scratch, renovating, or living in an older Mountains home, we can all be more resilient by regularly maintaining our buildings and our gardens, and having a clear plan.

As Nigel says, “We have to prepare for the worst and hope for the best.”

Part Two of this article will focus on gardening and landscape for bushfire.

Bushfire Resilient Design – Home and Garden was sponsored by the Katoomba Tool Library Toolo

Nigel Bell is an architect specialising in sustainable building. His practice, ECOdesign Architects, has represented the Australian Institute of Architects on the three ‘bushfire’ Australian Standards regulations (sprinklers, bunkers and construction) as well as giving evidence for the 2020 Royal Commission. For more on Nigel Bell and ECOdesign go to: https://www.ecodesignarchitects.com.au/

See Nigel Bell’s article in Sanctuary here: Beating bushfire: retrofitting for safer homes in fire-prone areas.

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.