Sue Bell in her Katoomba garden (Liz Durnan)

By Liz Durnan

The garden is the first line of defence in a bushfire, but that doesn’t mean sacrificing liveable spaces for the rest of the year. Landscape architect Sue Bell explains how we can balance good garden design with sound bushfire principles.

This story is the second in a two-part series on Bushfire Resilient Design – Home and Garden. You can read part one here: Building for Bushfire

It’s easy to see what appeals to Sue Bell as I stroll through her garden – it flows naturally from her heritage home in South Katoomba with views over The Gully and to the valley beyond.

Clearly it performs many functions. There’s a multi-coloured tree house for the grandchildren, a productive veggie garden, an inviting lounge that captures the morning sun while we sit for coffee, and an extensive grassy area that’s supported the feet of many partygoers over the years.

But Sue, and architect husband Nigel Bell, are all too aware of the potential risk to their property in the event of a bushfire advancing from the valley below, sitting as it does, atop the slope.

Sue and Nigel bring years of extensive design experience to a series of workshops, Bushfire Resilient Design – Home and Garden. The one I attend is at Nigel’s Katoomba studio at the rear of their property and I’m visiting again a few days later to find out more.

Slideshow from the Bushfire Resilient Design – Home and Garden workshop.

Design for function

Sue is as passionate about gardens as she is about bushfire protection, and she takes me through her principles for designing a garden.

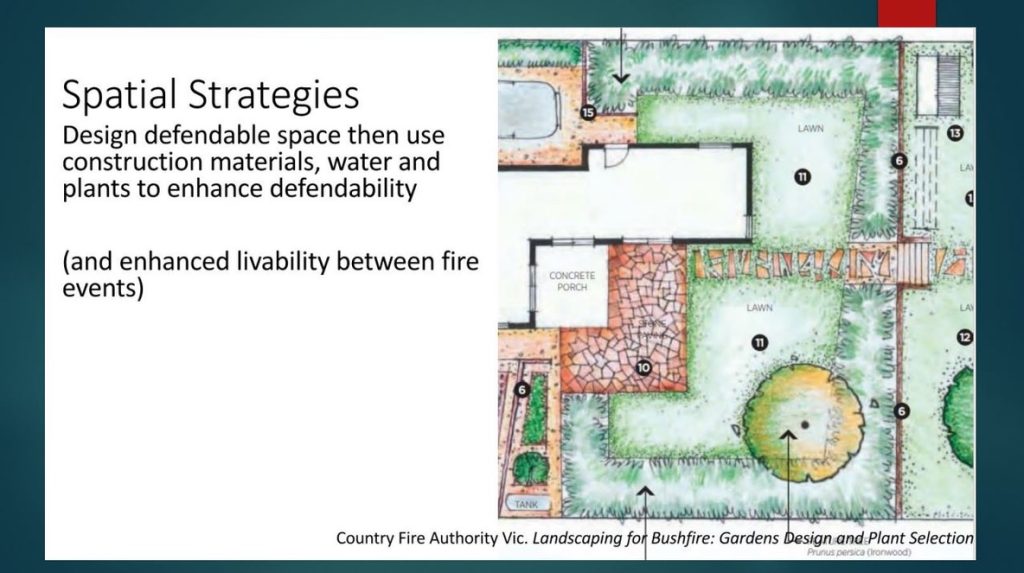

“You have to start with spatial set out,” Sue tells me. “When you say garden design, people immediately jump to plants, but plants are just one of the tools.

“First you need to identify what all your needs are, and the design is the process of finding the solutions to those needs. If you’re like me, you might have a need for social space, or your needs may be largely productive.”

Once you have listed those needs, she suggests identifying the species to plant, as it’s plants that will mostly shape the garden. While natives have their place, Sue prefers a mix of natives and exotics when selecting plants both for function and bushfire protection.

Regarding what species are best to defend from bushfire, there are no hard and fast rules because a number of factors play a part in plant selection and should be researched on a case-by-case basis to find out what’s appropriate.

Slideshow from the Bushfire Resilient Design – Home and Garden workshop. Illustration by Greg Gaul

Where the wind blows

It’s not just about what we plant that matters, but where we plant, determined by location. “It’s variable, even in the Mountains, and every site is different,” Sue says.

Sue’s husband, architect Nigel Bell who has worked extensively on designing homes for bushfire-prone areas, agrees. “Number one is to know what direction a fire is likely to come from. It’s typically northwest to northeast, but can be influenced by other factors, such as having a gully on the property.”

Once we know this, we can moderate what we grow in that area, particularly flammable species.

“We live in the Blue Mountains because we love our trees and vegetation, but we do need to be very careful with our landscape design,” Nigel says.

“Don’t just put trees everywhere. Don’t have them overhanging buildings and gutters. That’s what may ignite and cause you to lose your house.”

When thinking about home and garden layout, Sue emphasises the importance of easy access and exit points and identifying more than one if possible. These should be located away from where a bushfire is likely to approach.

Be water-wise

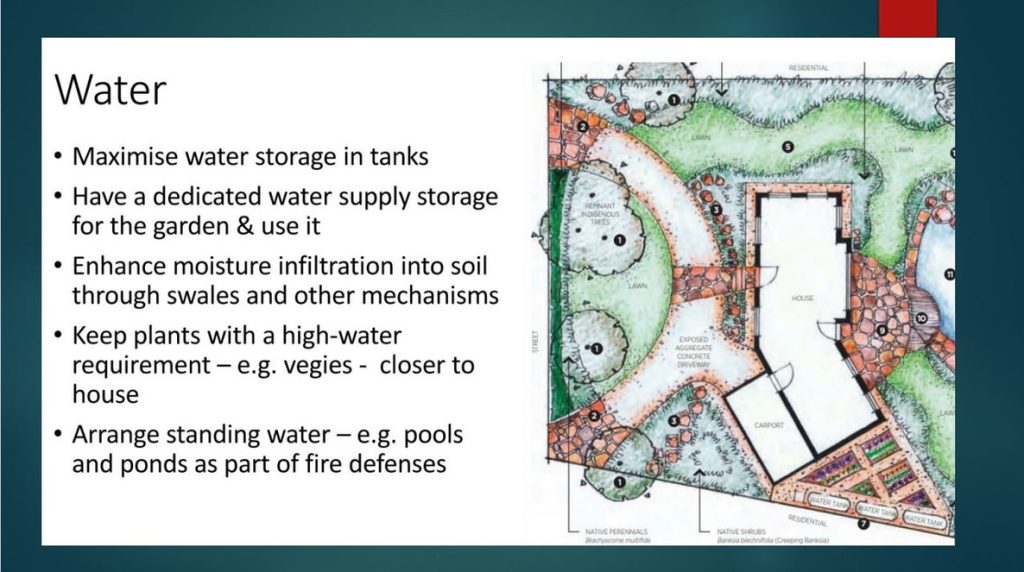

The issue of moisture comes up repeatedly throughout the workshop. “Being really canny with water is crucial,” Sue says. This includes preparing with plenty of water sources and the ability to saturate everything ahead of a bushfire.

She cites the famous photo, from the 2019 NSW south coast bushfires, of a well-watered mulberry tree credited with saving a cottage in the bush. The bright verdant green of the forty-year-old mulberry tree stands in stark contrast against the backdrop of incinerated bushland.

The property’s owner Brett Hawkins told ABC News the heat of the fire shifted and saved his house partly because he had heavily watered the tree in the period before the fires and partly due to luck regarding which direction the fires came.

“I’ve seen aerial photos of wet gullies where everything is burnt to a cinder to halfway down the slope and everything beyond the creek is wet and fresh and green,” Sue says. “So, maintain your garden with a level of moisture and make sure your plants are hydrated as much as they can be.”

That’s not always easy when fires often come after drought and water is at a premium. This is why gardens should be designed with water in mind, harnessing as much of it as possible, via roofs, and maximising its storage with rainwater tanks, pools and ponds. It’s important to locate them thoughtfully, too, on the side where a fire is likely to approach.

The next step is to consider mechanisms to get that water into your garden, quickly if needed. Sprinkler systems around the home and in the garden are a good idea, but soaker hoses are even more efficient to keep everything wet before, and during, a fire.

During the landscaping phase, it’s also advisable to maximise infiltration, such as incorporating swales – surface ditches that allow the water to penetrate. Many soils dry out, says Sue, and become hydrophobic, so they repel water, and it doesn’t infiltrate.

Slideshow from the Bushfire Resilient Design – Home and Garden workshop.

Rock hard surfaces

One of the most important ways we can build defences for bushfire, which is becoming increasingly recognised in regulation, is by creating non-combustible surfaces directly adjacent to the house. For at least a metre if possible, Sue says.

While hard surfaces may not be to everyone’s taste, we can compromise between the softness of plantings and hard surfaces, by focusing the hard surfaces close to the home and in the likely direction of a fire. Getting the balance right comes by combining the two and prioritising what’s most important.

“I’ve tinkered with that somewhat in my own garden where I’ve planted narrow beds next to the house, but only very low plant material that I can easily maintain to reduce its flammability,” Sue says.

Another key defence tool, particularly for those at-risk sites high on slope, is to terrace gardens with low retaining walls of non-combustible materials, e.g. brick or stone.

This has two functions: keeping the soil level just below the top of the retaining wall holds water, even if it’s just a couple of centimetres. Secondly, those vertical surfaces of non-combustible material act as a radiation shield if a fire does ever approach up the hill.

And as an added bonus, “terracing makes much more liveable space, garden space. You can sit on it, you can put furniture on it.”

Slideshow from the Bushfire Resilient Design – Home and Garden workshop.

Living with nature

While it might be tempting to reduce vegetation as much as possible, Sue understands that no one wants to live in a ‘biological desert’.

Lawns have become unfashionable, she says, but she sees a place for grassy areas within the ‘rooms’ of a garden: “Lawns make great social space for parties or ball games, and they can act as ‘defendable space’ in a bushfire.”

Slideshow from the Bushfire Resilient Design – Home and Garden workshop.

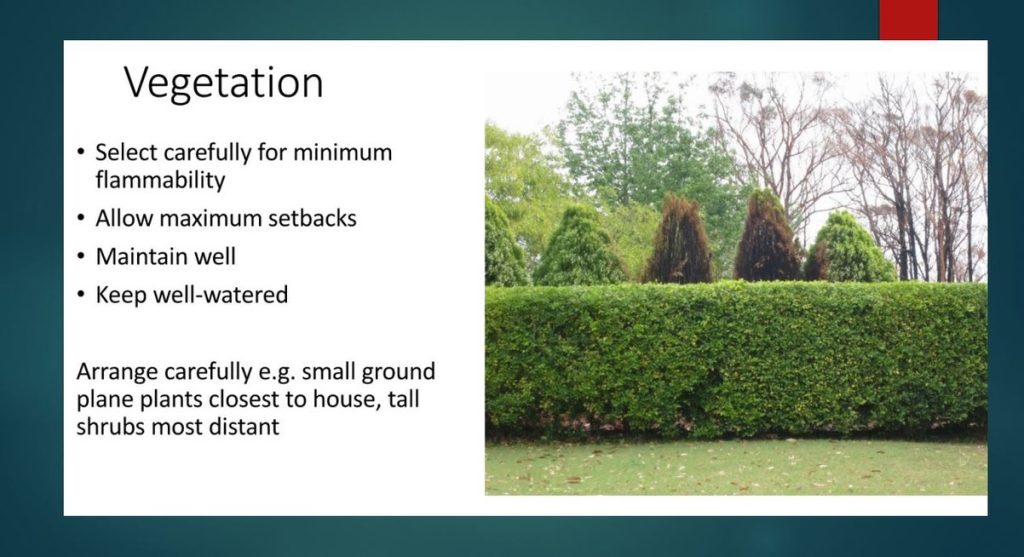

As with homes, maintenance of the garden is as important as design. You don’t have to remove all your structures, such as pergolas with deciduous vines that function as valuable shade, but it’s vital to keep them well maintained, regularly removing twiggy growth. Even a tree or shrub listed as low-flammable, will be flammable if it’s allowed to become woody and overgrown.

The same goes for well-selected, well-maintained hedges that can be useful in bushfire defence, depending on the species. Sue is re-examining elements of her own garden in light of research on vegetation, planning to remove a myrtle hedge that she now understands to be a fire risk.

As a garden designer and nature lover, Sue is dismayed by the urge to rip everything out, but recognises different value systems.

“To one person a garden is all about fuel, while to a gardener it might be all about how much you can plant. But for many people, the garden is exceptionally important and sometimes we underestimate this.

“A little bit of nature is really important and in between a crisis that might come once every few years, we have a life to get on with.”

Read part one of this two-part series on Bushfire Resilient Design – Home and Garden: Building for Bushfire

Bushfire Resilient Design – Home and Garden was sponsored by the Katoomba Tool Library Toolo

Susan Bell is a retired landscape architect who has made her contribution to bushfire design and recovery. She has qualifications in horticulture, landscape design, permaculture, environmental management and strategic planning, with a Masters degree in the latter. From 2007 until 2020 she was employed as Principal Urban Designer at the Blue Mountains City Council.

Nigel Bell is a sustainability architect and consultant who has been at the national forefront of bushfire resilient design, construction and recovery for several decades. His practice, ECOdesign Architects, has represented the Australian Institute of Architects on the three ‘bushfire’ Australian Standards regulations (sprinklers, bunkers and construction) as well as giving evidence for the 2020 Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements, sometimes referred to as the ‘Bushfires Royal Commission’.

You might also like to read Future-Proofing with Water in a Japanese-Inspired Garden

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.