Regent Honeyeaters (Dean Ingwersen)

By Liz Durnan

Liz Durnan spoke to artists Ro Murray and Mandy Burgess, and Blue Mountains World Heritage Institute CEO Jane Powles, about a heartbreaking story of near-extinction and how we can help save the lost song of the Regent Honeyeater.

Any story of near extinction is heartbreaking, but the plight of the Regent Honeyeater has an extra poignant twist when we consider what’s at stake. We may not only lose the bird forever, but also its distinctive song.

This potential tragedy captured the imaginations of artists Ro Murray and Mandy Burgess when they read about a study by ANU researcher Ross Crates. The Regent Honeyeater was once widespread throughout southeastern Australia. In the last fifty years its numbers have plummeted, possibly to as little as three hundred, putting this beautiful bird in danger of extinction.

Mandy has learnt that an estimated 85 per cent of the Regent Honeyeater’s natural woodland habitat has been cleared for agriculture and many of its predators have prevailed. Now there aren’t enough mature male birds to teach the young males the mating song they need to attract a mate and continue the species.

Artists Ro Murray (left) and Mandy Burgess (right)

In an even sadder twist, many of the birds now imitate the call of other birds, meaning their once complex song has become corrupted.

“It’s a bird that flies widely in flocks,” Mandy says. “And the flocks provide protection but without that and particular flowering trees, the population has dropped so that they don’t have the protection of their flock anymore.”

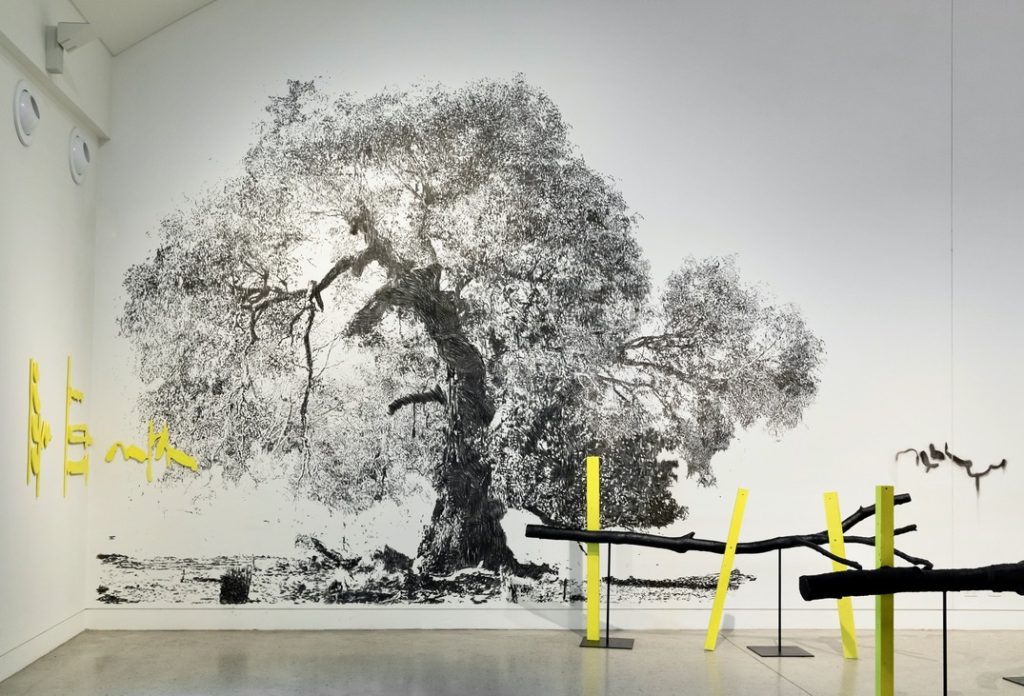

Ro and Mandy were so moved by the Regent Honeyeater’s story they applied to exhibit a multimedia exhibition at the Blue Mountains Cultural Centre in Katoomba earlier this year. The exhibition, supported by Birdlife Australia, Taronga Zoo and the Blue Mountains World Heritage Institute, investigated the iconic bird’s song, its habitat and survival, and the fight to save it.

In addition to multimedia elements of sculpture and charcoal drawings, Ro and Mandy, with the support of the Blue Mountains World Heritage Institute, were successful in being awarded a Create NSW grant to commission a composer to represent the musical element of what they were trying to convey – the ‘lost song’ of the Regent Honeyeater. The charcoal wall drawings represented transcriptions of the spectrographs of the birdsong, which together with audio recordings, were used by the Blue Mountains composer Felicity Wilcox to create a moving elegy with voice, clarinet and marimba to accompany the exhibition.

Lost Song (Silversalt)

Parallel to this, the Cultural Centre held a seminar on the Regent Honeyeater hosted by Jane Powles of the World Heritage Institute. It was attended by a multitude of experts: academics, artists (including Ro and Mandy), scientists, and birding guide Carol Probets.

Carol highlighted how the Regent Honeyeater moves between isolated patches of woodland to find blossoms. Carol has tracked birds fitted with radio devices in order to understand their seasonal movements in the Capertee and in the Burragorang Valley, and she has worked with the team at the Australian National University to conduct surveys on the Regent Honeyeater.

Birding guide Carol Probets counting Regent Honeyeaters (supplied)

Mandy recalls Carol’s description of the Regent Honeyeater as a ‘flagship species’. In conservation terms, this means a species chosen to represent a specific cause and raise awareness.

Mandy agrees: “It’s like the koala. It’s a beautiful bird with a beautiful song and its environment is shared by lots of other species that are also in decline.”

Jane Powles echoes this concern, warning that if we lost the Regent Honeyeater, there would be a ripple effect for other species:

“It’s one of the species at the tip of the cliff,” Jane says. “Should this go, there’s a cascading effect of loss amongst a range of other species.”

The converse is also true: “So, if we’re able to protect the environment for the Regent Honeyeater, it means that there’s that cascading protection for a range of other species.”

But further habitat loss, and developments such as the long proposed raising of the Warragamba Dam wall, pose ongoing concerns for those trying to protect the Regent Honeyeater.

The seminar panel agreed that raising the dam wall would adversely affect crucial riparian habitat for the birds by changing the frequency and duration of flooding, further diminishing food availability throughout the year.

“There are very few breeding grounds left,” says Ro. “And this will take away one of those few.”

Since interviewing Ro, Mandy and Jane for this piece, news came in that the new NSW state government had shelved plans to raise the Warragamba Dam wall. That’s at least some good news for the Regent Honeyeater and shows how a strong and sustained campaign of resistance can make a difference.

According to Ro and Mandy, art is one of the ways to raise awareness about these critical environmental scenarios that ultimately affect us all.

Jane Powles agrees that art is a valuable way to engage audiences in conservation issues. “It’s that beautiful intersection between science and being able to translate that into art; to tell the story in a way that people who wouldn’t normally engage in the science can actually grasp the loss of this space.”

Art helps people to use their imagination too, Ro says. “It is about extinction, which you have to imagine you can’t come back from. We might have birds survive in the zoo, but they’re not going to survive in the wild, unless something is done.”

Lost Song (Silversalt)

“And so for us, there was a process, how we developed the exhibition. We had the loss of habitat which were the fallen trees, the walls were interpreting the translations of the spectrographs of the songs. It’s like a requiem, but we don’t want to say that. We want to be hopeful.”

They all agree that there is hope and Jane highlights some of the inspiring work that’s being done.

“There is a beautiful story,” she says, “about Kara Stevens from Taronga Western Plains Zoo who’s working in the recovery program for the Regent Honeyeater.

“She talks about the breeding program and the recovery and there’s a period where they actually teach the new chicks the song. It was just fascinating to hear her describe that process.”

Ro agrees. “As part of the program, songs are recorded by scientists from ANU’s Difficult Bird Research Group and Kara was talking about a couple of live tutors that they use in Dubbo. They take a couple of months to adjust to being in the zoo, but then they are singing and the younger birds are learning.”

Jane recalls joyful stories from the panel about birds released from the program into the wild that are found a month later to be thriving and singing in their new environment.

How to get involved

There are ways for people to become involved and help to bring this bird back from the brink. Anyone can donate to causes that support the Regent Honeyeater, including Birdlife Australia, Taronga Conservation Society, and the Blue Mountains World Heritage Institute which, according to Jane, is involved in efforts to support conservation of the bird’s habitat:

“We do conservation research, so understanding what the threats are to the local environment and also what the land managers’ issues are. So we work very closely with National Parks and Wildlife and Blue Mountains City Council to find out what the management needs are in relation to those threats and that research helps them develop their work plans.”

People can get involved in a hands-on way with the bi-annual planting programs that help to rebuild the habitat for the Regent Honeyeater. There are details of upcoming volunteer plantings here on the Birdlife Australia page.

Students visiting the Capertee Valley and learning more about the Regent Honeyeater (Lis Bastian)

All agreed that it can help to get involved by writing and supporting politicians who make a stand against development:

“The rates of land clearing have skyrocketed,” says Mandy. “Because of changes to legislation and rules regarding clearings.”

Jane suggests engaging with politicians you know care about a cause: “The way I like engaging with political parties is asking what you can do to help, particularly when you know somebody cares about a cause.”

For Jane, talking about issues and raising awareness is key to success. “It’s very much about that connection to humanity and our existence being completely integral to the environment and sustainability and planetary health. You can’t separate them. It’s changing the conversation and the shifting of the narrative.”

To see the full panel discussion, go to: https://youtu.be/yxwFxKchDFc

Learn more about the Regent Honey Eater here: https://birdlife.org.au/projects/regent-honeyeater/

Hear more from Ro Murray and Mandy Burgess on the exhibition, as well as composer Felicity Wilcox:

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.